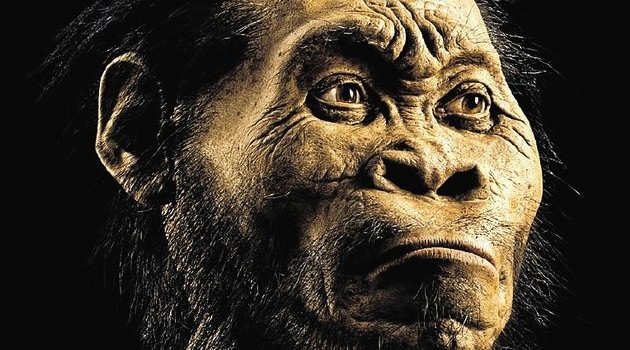

Homo naledi is a racist plot using pseudo-science to link Africans to subhuman, baboon-like creatures.

Homo naledi is a racist plot using pseudo-science to link Africans to subhuman, baboon-like creatures.

It sounded mad, and Mathole Motshekga and Zwelinzima Vavi were roundly jeered on social media for expressing it. I joined the chorus, because gigantic ignorance should not be tolerated in our leaders. But I can also understand where such paranoia comes from.

Even as Facebook howled its derision, racists gloated over pictures comparing Homo naledi to Robert Mugabe or Jacob Zuma. It is dangerous to discount the theory of evolution, but it is also understandable when most of your contact with the idea of primitive, dark-skinned knuckle-draggers has come not in the form of scientific debate based on our common humanity but as the poisonous barb on a white supremacist insult.

It made sense. But the more I read the arguments, the more I realized that only some of the objections were bound up with the awful legacy of racist European pseudo- science. The rest, it seemed, were religious, and bridged both class and race. It turns out that a huge number of South Africans, perhaps even a comfortable majority, reject Homo naledi as an ancestor because they believe that a monotheistic god created them in its own image.

It forced me to imagine their experience of our country, of its past and present, of everyday events. What, I wondered, is your average day like when you believe that science is either a racist tool or simply wrong? What kind of relationships do you form with people if you believe that they are God’s most perfect creation, or, as claimed by Motshekga, they were created before the universe existed?

I can’t speak for my compatriots, but I think if I believed those things, I would feel the most delicious entitlement. To know that you are the reason for all existence, that everything in the universe is a prop for you to use in the God-scripted drama of your life – ye gods, how glorious!

To an atheist like myself, who believes that the theory of evolution is currently the best explanation we have for how we got here, it all starts feeling a bit mad. But I also concede that many of my beliefs would seem bonkers to millions of my compatriots.

This month we are being urged to reflect on something called “heritage”; to collect a bundle of historical and culture goodies we have inherited and to show them off to each other as some sort of morale-boosting exercise. The assumption, of course, is that these goodies are real: concrete truths, sensible beliefs and practices, true histories. But how real is any of it when we live in a world saturated with fantasy and projection, where contradiction masquerades as conviction?

In South Africa, you don’t have to wander far before the ground under your feet turns to quicksand.

Our leaders talk democracy, then hand over the podium to feudal kings who talk about blind allegiance.

Revolutionaries call on us to be suspicious of non-African influences, in the same breath that they quote a German philosopher and adjust their berets, modelled on a Cuban and made in China, before driving to church in a Japanese car to worship a Jewish Palestinian who was put to death by Italians who whose life story was written by Greeks, preserved by Irish monks, and eventually brought to Africa by English blokes.

Gloomy whites urge blacks to “get over the past and move on” while jealously tending the flame of their resentment over the Boer War or the treachery of FW de Klerk.

Next week the country will suffer ‘Braai Day’, a carcinogenic corporate kerfuffle designed to bring South Africans together by banishing women to the kitchen, sending men to the garden, and completely excluding vegetarians and people who like their chicken cooked properly. It’s based on the assumption that we all need to share common values because we occupy the same country.

Which, of course, relies on the assumption that South Africa is actually a country. Cue even more contradictions, as passionate opponents of colonialism put hands on hearts and declare their love for the arbitrary stretch of land demarcated by colonial map-drawers in London. It would be funny if it didn’t sometimes become bloody, when, for example, Southern Africans from the imaginary place called “Zimbabwe” cross the imaginary line into the imaginary place called “South Africa”. Xenophobia is real and brutal, but I’m not convinced it is entirely about fearing otherness. It is also deeply bound up with unthinking, obedient belief in borders and countries; about crossing that imaginary line. When someone moves the 1 700 kilometres from Musina to Cape Town, nobody blinks. But move the 25 kilometres from Chamumnanga to Musina and you are considered utterly alien.

Perhaps this is why Homo naledi seemed like something worth celebrating. It felt like a piece of truly common history. And yet if you believe in evolution, is this really a win? Nothing that is good about modern Africa existed in those desperate little animals. They might have been (almost) human, but mostly they were food. We can’t begin to imagine how little they knew about their world, or how abject their short, frightened, painful lives were. They passed on almost nothing to their children except their DNA and their fleas.

When it comes to heritage, I’m as confused as the next naked ape. But I know I’m not going to celebrate Homo naledi as part of my human heritage. Instead, I’m going to celebrate that I have absolutely nothing in common with that ancient prototype. I’m going to celebrate inventors, philosophers, artists, even a few warriors. Above all, I’m going to pop a peer-reviewed headache pill, wash it down with pasteurized milk and celebrate the scientists who try to drag us out of the muck despite our determination to return there.

One day humans will cure brain death. If we decide to keep our organic bodies, ageing will become optional. I’m very grateful that I won’t be alive when that happens. But when it does, our descendants will look back on us and perhaps see us more clearly than we see ourselves: as a small flame flaring in the dark, briefly casting shadows on the wall – an illusory panorama of phantoms and projections – before we flicker out. They will read our assertions about who we are and where we’ve come from, and hear their true meaning; that we declare, “I am this!” because we know that one day we’ll be like Homo naledi: nothing at all.

*

A slightly shortened version of this column was first published in The Times and Rand Daily Mail.

Thanks. Such a great articulation of what a lot of us feel. Celebrate moving forward, not looking backwards.

LikeLike

Who the heck braai’s chicken?

LikeLike

Remember when Tom Eaton used to be funny?

LikeLike

No.

LikeLike

Yep. *sighs*

LikeLike

Well said. Spot on.

LikeLike

Good job Tom. So well articulated on many a tricky subject. You knock this out the park! Great read!! thanks a mill.

Got any scripts?

LikeLike

“To know that you are the reason for all existence, that everything in the universe is a prop for you to use in the God-scripted drama of your life – ye gods, how glorious!”

Hmmm, I don’t think true deists are that proud of themselves. The belief of a higher power, and therefore to realise that your life is part of a much bigger picture, should bring about significant amount of humility to the average person.

Interesting and well written piece, nontheless.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. I disagree, though: I think that true deists still get to be the star in a story that is all about them, even if they cast themselves as a tiny part of a greater whole. A bit like fishing for compliments on a cosmic scale: “Oh, I’m just a little nobody”, demanding the reaction, “No! You’re amazing! Because God made all of this with you at the centre of it!”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Conversely, it’s quite arrogant to think that there is no higher power simply because we can’t prove it. That suggests humans are so smart that we should be able to discover everything. (See how atheists can also make things about themselves?)

For the most part I don’t think religion is or should be a point of bragging for believers. Of course, you’ll get a few who brag about being made in God’s image blah blah while some atheistic brethren brag about being part part of the species that were “naturally selected”. Both cases speaks to the proud nature of humans and I think in both scenarios, people have missed the big picture they supposedly believe in.

LikeLike

This column was unnecessarily emotional for me this Monday morning.

I left it feeling disquieted and uncomfortable.

At first read, I was practically an altar boy serving in the church of Eaton, where morality is relative yet logically immune to judgment and molestation by lascivious elders.

The threads and connections you employed to point out the obvious desperation we all suffer to find commonality resonated with me and non-conforming bearded atheists the world over.

I was also very relieved when you acknowledged my singular adherence to non-conformity through your musings in that self deprecating tone unique to thinkers like us.

Eeyore, had he cared, would’ve grimaced from his literary grave (the closest he would ever come to a smile.)

So pleased was I at our shared understanding of the universe, that I nearly trimmed my beard to within a single finger’s width above my Adam’s apple in ironic deference to this apparent resonance.

I revelled in the cynicism with which you exposed bigotry, irrational belief and ignorant subscription to badly informed dogma premised on distorted fact and obvious manipulation.

I chimed in heartily with the chorus of intellectual and academic (often misunderstood as the same thing) derision among those who understand the “true” references to cuban beret wearing and German philosophy

Note: I didn’t go to University so all I could do was chime. I can’t genuinely attest to the veracity of any of these references. I am however, very good at nodding in gleeful agreement.

I was almost deafened by the loud “Tsk” carefully enunciated at university canteens around the country.

I could feel my carefully coiffed hair blown back with every latte fueled sigh and coffee-shop eye roll.

This is where I belonged. In the loneliness of my weary outrage. Heard only by an enlightened few for a fleeting moment before it is annihilated by clever analysis and pithy retorts in comment sections.

I was particularly impressed by your slick segue into the perennial deconstruction of social “truths” derived from the vociferous and very vocal anger at Vavi and Mothshekga’s comments. “Political morons!” I heard them chant. “Uneducated idiots!” I replied.

But I digress.

After the euphoria of my thoughts and beliefs being given a voice by your eloquent missive, a discomfort came over me.

I read your column again. And then again. Slowly the gloss wore away when my eyes unwaiveringly trained on that mildly self denigrating (Thesauri reveal such delicious irony) opening paragraph:

“‘Homo naledi is a racist plot using pseudo-science to link Africans to subhuman, baboon-like creatures.’ It sounded mad, and Mathole Motshekga and Zwelinzima Vavi were roundly jeered on social media for expressing it. I joined the chorus, because gigantic ignorance should not be tolerated in our leaders. But I can also understand where such paranoia comes from.”.

The rest of your pensive yet eloquent and often amusing diatribe aside, this is where it all fell apart for me.

Do I really subscribe to this parallel form of dogma often masquerading as reason? This deconstructionist cynicism (I’m sure there is a more acceptable and palatable philosophical moniker hidden in the annals of academic literature somewhere) that allows me to neatly sidestep the chaotic nature of life around me?

The answer is unequivocally “YES!”. But, then again, maybe not.

LikeLike